The cult of normal

For centuries, society has treated normal as a fixed standard – shaping science, culture, and psychiatry around an idea few truly fit. What began as a mathematical concept became a way to define belonging. But if normal is an illusion, why do we still let it define us?

I've always felt different than other people. For decades, this created an internal contradiction – on one hand, I didn't feel normal, but simultaneously, I couldn't figure out what it even meant to be normal. It was like trying to measure myself against a ruler with no markings.

"We accept the reality of the world with which we're presented," says Christof in The Truman Show, reflecting on why the main character in the movie never questioned his artificial world. Like Truman, I accepted the narrative that I was somehow off without questioning who created the standard I was failing to meet. I had unknowingly been indoctrinated into the cult of normal.

It's only recently that I've started challenging my own reality. With the benefit of hindsight and a year of self-reflection following my ADHD and autism diagnoses, I've begun to understand why I've never felt normal. It stems mostly from navigating a world built for the predominant neurotype where the constant messaging from media, educators, clinicians, and well-intentioned people who frame autism and ADHD as deviations from some arbitrary standard of norm. Their language subtly reinforces the idea that there's a right way to be human, and I'm somehow missing the mark.

So I thought I'd do a deep dive into the concept of normal, how it's changed over the years, and whether such a thing even exists at all.

The origins of normal

The word normal derives from the Latin norma, which refers to a carpenter's square or rule. The adjectival form normalis meant 'made according to the square'. By the 17th century, this concept was used to describe perpendicular angles in geometry, adhering to a fixed standard. By the 18th century, the word began to be more broadly used in science and medicine.

But it was the 19th century when the word began to be used in a way that shifted to have a social and cultural lens. Normal became more about societal expectations not just scientific principles and later in the century it was used, especially in medicine and psychology as a way to contrast the abnormal. We start to see the use of normal behaviour and normal family structures and normal intelligence. All suggesting that anything outside of this norm was, by default abnormal or wrong.

French historian and philosopher Michel Foucault argued that schools and hospitals weaponised the concept of normalisation to enforce compliance through surveillance and categorisation. For example, pathologies deviating from Victorian norms were seen as madness, conflating moral and medical judgement.

Human evolution

Evolutionary biology challenges the notion of a singular normal human being. Homo sapiens emerged around 300,000 years ago with diverse cognitive strategies adapted to survival. Neanderthals, for example, had larger brains with potential differences in visual and motor processing, while early humans developed syntactic language and symbolic thought.

These variations were adaptive, not aberrant, a theme echoed in modern debates on neurodivergence. Some researchers suggest that traits now associated with ADHD may have been advantageous in hunter-gatherer societies, favouring quick adaptability, risk-taking, and rapid responses to stimuli. Evolutionary psychiatrist Randolph Nesse argues that traits persisting across generations likely provided survival benefits, even if they no longer fit smoothly into modern environments like classrooms and offices.

From demons to dopamine

There's consistently been a danger in the use of the word normal when it moved from things that could be clearly measured like angles to things that can't like humans.

Throughout history, psychiatry's shifting standards, for example, shows how abnormality has been a moving target that is shaped by culture and power. Normal is seen today as the typical, the expected, the conforming. Over time that has meant abnormality taking on a more negative connotation, suggesting it's undesirable or wrong. If we look at it over the centuries:

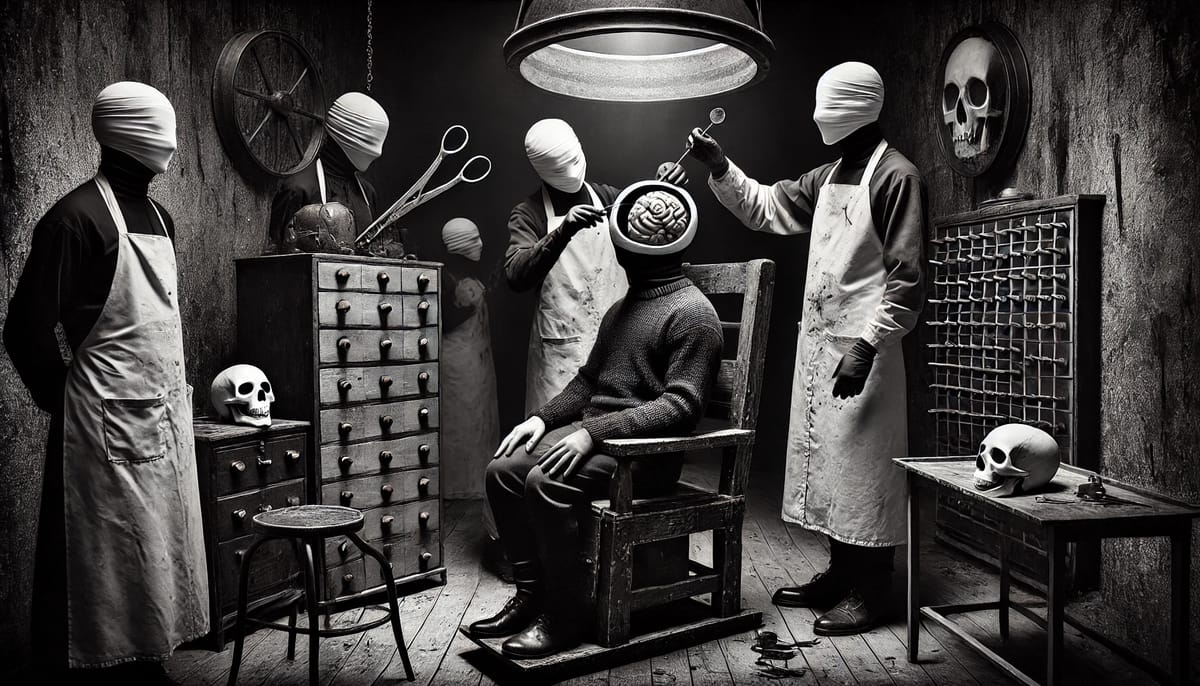

Supernatural explanations (Pre-18th Century)

Abnormal behaviour was often attributed to demonic possession or divine punishment. Those ideas were associated with trepanation, or in its much friendlier description, drilling a hole in someone's skull to release evil spirts.

Moral and biological models (18th-19th century)

The Enlightenment recast mental illness as a medical issue. While French physician Philippe Pinel advocated for humane treatment for patients instead of them being chained up and Emil Kraepelin helped classify mental disorders into categories, the intellectual and cultural movement may have been progressive for its time, but also reinforced social control. Suggesting, for example, that 'outspoken or independent women' were mentally ill.

The DSM era (1950s-present)

Maybe it's a little strong to say that the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) codifies normalcy through committee consensus. But, you know, I'm going to say it anyway. ADHD first appears as a hyperkinetic reaction to childhood in DSM-II (1968). Allen Frances, who was the lead editor of the fourth edition of the American Psychiatric Association's DSM, later said in an interview "there is no definition of a mental disorder. It's bullshit. I mean, you just can't define it. These concepts are virtually impossible to define precisely with bright lines at the boundaries".

One of the clearest (and most damaging) examples of the DSM's subjectivity was its classification of homosexuality as a disorder until 1973. The entry in 1968 was:

302.0 Homosexuality. “This category is for individuals whose sexual interests are directed primarily toward people of the same sex and who are either disturbed by, in conflict with, or wish to change their sexual orientation.”

Grouped under Personality Disorders and Certain Other Non-Psychotic Mental Disorders in the DSM-II, this classification remained until the APA literally voted on whether people's sexual orientation constituted a mental illness.

In reality, people weren’t disturbed by their sexual orientation – they were more likely disturbed by the societal stigma that branded them as abnormal. The DSM didn’t just reflect this stigma; it legitimised and reinforced it through medical authority, creating a circular system where psychiatry and social attitudes fed into each other, like the worst toxic relationship.

Lies, damn lies and statistics

Today the idea that normal equates to statistical averages is what many people believe, but fundamentally misunderstands human variation. Consider intelligence. When researchers examined various cognitive abilities (memory, reasoning, processing speed), they found that less than 3% of people were actually average across all dimensions. Most of us have cognitive profiles with peaks and valleys – strengths and weaknesses that diverge significantly from any mythical average person.

In reality, the emphasis on statistical normality creates a situation where almost no one is normal by definition. This is why the neurodiversity movement, born from 1990s autistic self-advocacy, rejects the pathology paradigm entirely. Rather than treating differences like ADHD or autism as disorders to be fixed, this perspective frames them as natural variations in neurocognitive functioning, more like left-handedness than disease.

Normal has never been normal

The irony isn't lost on me that I spent decades feeling abnormal, only to realise that statistically speaking, nobody is normal.

We're all living in our own cult version of The Truman Show, devoted followers of a doctrine of normalcy that no one can define. We're convinced there's a perfect standard out there while the reality is it's all manufactured. Just like Truman eventually realised his normal world was an elaborate set, I'm coming to realise that normal itself is just an artificial construct with good lighting, clever camera angles, and a congregation of believers who never question the scripture they're following.