Lives without imagery

The Big Interview: Tom Ebeyer of aphantasia.com on living without visual imagery. From realising he couldn't picture anything in his mind to creating a global platform, he’s changing how we think about imagination.

In 2015, Carl Zimmer of The New York Times wrote a piece titled Picture This? Some Just Can’t, marking one of the first instances the word aphantasia appeared in mainstream media. Earlier that month a research paper, Lives without imagery – Congenital aphantasia, made it into the journal, Cortex.

That paper, written by Adam Zeman, Michaela Dewar and Sergio Della Sala, coined the phrase aphantasia, which is the inability to visualise, often referred to as 'image-free thinking'.

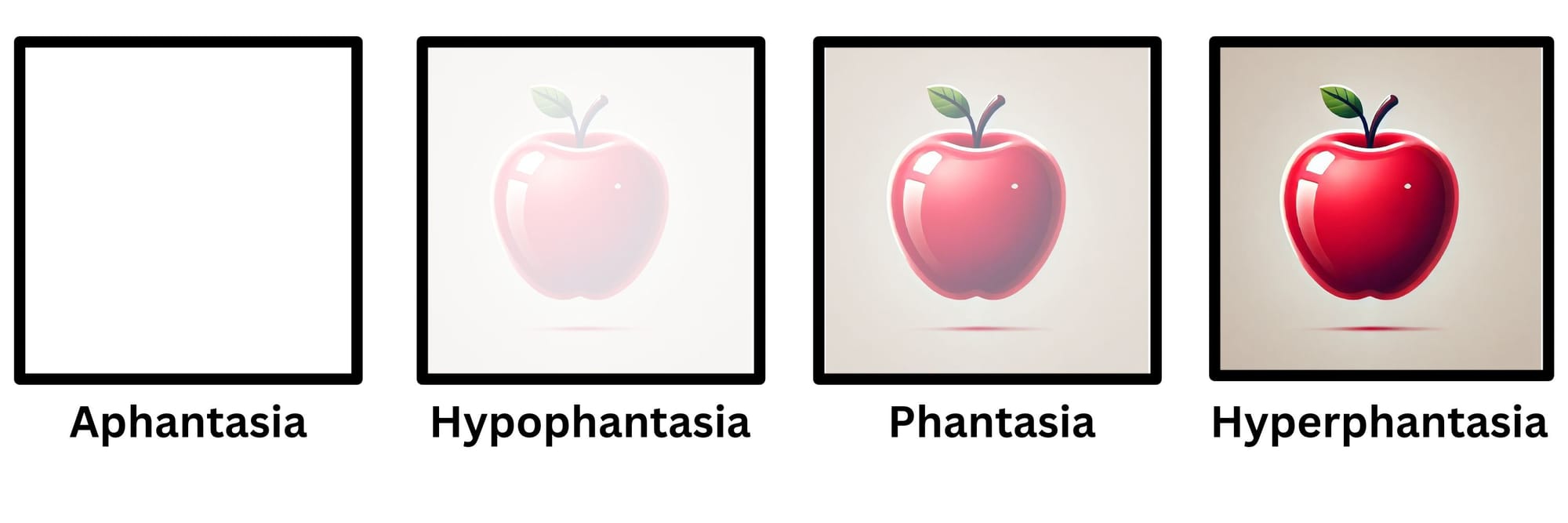

For most people when they close their eyes they can create a mental image in their mind’s eye. If you’re part of the majority of the population who can see something and I asked you to close your eyes right now and picture a red apple or your favourite memory, you’re likely to be able to see it on a spectrum from a little fuzzy right up to the human equivalent of ultra high definition.

For those of us with aphantasia, we see nothing. We lack the ability to picture at all in our mind. In early 2024 after being asked an innocuous question at an event, I realised that not being able to picture anything in your mind's eye isn't that common.

When I tried to find out more online, I encountered the same mental blankness, this time it was trying to find a term I didn't know existed.

At one point I thought I was gaslighting myself, having assumed that everyone else also experienced nothing when they closed their eyes. When was the last time you had a conversation with someone about what goes on in their head?

After a lot of Googling, I eventually found the term and the website Aphantasia.com. Its founder, Tom Ebeyer, was one of the people featured in that NY Times article in 2015 who had aphantasia and someone who, when he first realised it about himself, also couldn’t find anything because it didn’t even have a name to find back then.

“When I first discovered that other people didn't visualise, there wasn't a name for it yet,” said Tom, speaking to me from Canada.

“So aphantasia, as a term, was created in 2015 and I discovered I couldn't visualise, maybe around 2010. For the first four or five years I was like that annoying guy at the party that was asking everyone to close their eyes and picture a horse, and trying to get them to describe it.”

Rabbit hole

Ebeyer first discovered his condition at age 25 during a conversation with a friend who could vividly recall what someone had worn a year prior. She told him she could see a picture of it in her mind. Like me, he went to Google, but found nothing.

“I was obsessed with this idea, because I couldn't do it. And there was a little while where I was pretty upset about it, because I went down the Google rabbit hole, and pretty much everything that I read was like, oh, just you know, maybe try to meditate.

“Close your eyes and meditate, and then you can visualise or all these other kind of techniques that really just didn't work or resonate.

“It's fascinating how we can go so long in our lives without recognising these type of differences, because you don't really know what goes on in other people's minds. At least for me, for so long, I thought these things like visualisation, or when people say, ‘oh, just picture it’ that it was more like a metaphor, not something literal."

It upset him that he hadn’t met anyone else like him and most people were confused that he couldn’t picture a horse or his family or even what his future might look like. The rabbit hole took him to university professors at psychology departments across American universities but led nowhere. Then in 2013 he came across a paper by Dr. Adam Zeman from the University of Exeter.

Famous faces

Zeman's 2009 paper documented a patient who lost the ability to visualise after a medical procedure. That initial patient was able to perform well on problem-solving tests. Asking him to look at faces of famous people and name them, his brain was as active in the same regions as others. But, when they asked them all to picture a famous person’s face in their head, everyone else’s brain regions became active again, the patient’s did not.

Ebeyer reached out to Zeman and said he’d not had that ability his entire life. They did tests and experiments like asking him to count the number of windows in his childhood home or to answer what is a deeper shade of green – a blade of grass or an evergreen tree.

“We were discovering that, actually, I can do these things. I'm just doing it a different way. So then he [Zeman] wrote that paper called Congenital Aphantasia in 2015. I bought the domain aphantasia.com because I was so passionate about this and I really wanted to connect with other people and see if they were feeling the same way that I was at the time.

“The New York Times did a short article and I had people from all walks of life on all the social media platforms flooding my inbox basically saying that they had the same experience. And it kind of just really grew organically from that.”

Tom Ebeyer, left, grew up in Canada and went to university in the city of Waterloo (right, picture by Andre Renard)

Ebeyer grew up in Canada before going to university in a small university town called Waterloo, about an hour outside of Toronto. The city boosts a significantly higher median household income than Canada’s national average and before becoming well known for its tech companies (Blackberry is headquartered there) it was an insurance mecca. Since university he’s stayed in Waterloo but goes back and forth between the “cool little community” and Malta, where his family is from.

Previously involved in an incubator at Wilfrid Laurier University in nearby Kitchener for four years and more recently working in the world of blockchain, Ebeyer launched aphantasia.com to counteract a lack of online information about the topic. Clearly there was a need, today the site, which features articles, insights and a Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ) to allow you to understand if you have aphantasia, has about 1.5million visitors per year.

“We have the largest data set in the world now on visual mental imagery, at least about 1.25 million entries on the VVIQ questionnaire, so it has seen quite a lot of traction.

“I think there's huge momentum, especially on the research side. From where this was just a few years ago to now you're seeing research labs around the world really show interest in this, because there's a famous line going all the way back to Aristotle, which was that the mind cannot think without images, and that is a common, unspoken assumption in a lot of psychology and cognition research.

“You know that mental imagery or visualisation is kind of one of those inherent things that all people have. And so the discovery of aphantasia in a lot of ways challenges many different ways of looking at the human population and the diversity of it.

“So you're seeing a whole bunch of research in different domains. And so I think the momentum really is there, and that's very exciting. And it's not just in the visual sense, there's research happening in auditory and motor too.

“Even in physiotherapy and physical rehabilitation, motor imagery is a very common technique that's used with patients who need need certain forms of that rehabilitation. And so there's a sub segment of the population that current techniques don't work for.

“The discovery and research around aphantasia might help find some of those alternative techniques that might work and help people in different types of circumstances. So the application and area of research is quite broad.”

Negative sphere

Aristotle often appears in discussions on aphantasia, primarily for his use of the word phantasia, describing a unique mental capacity between perception and thought. Commonly translated as imagination, putting the letter ‘a’ in front of it denotes its absence.

“By it being inherently defined as you lacking or missing something, it automatically puts it into a negative sphere, and I think that belief can also be a little bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy. So if you're always looking for the negatives or the shortcomings, you tend to find them. But if you look for the positives, you might find some and I think there's a net benefit.

“There's different perspectives [on the use of language]. I tend to think it falls more in the category of without sensory imagination. You know, imagination is a really loaded and ambiguous term, because people use it in different contexts, or refer to different things. So for sure, people with aphantasia can be creative. They can create new ideas and concepts and build businesses and all those kind of things.

“There are lots of famous aphants – Craig Venter helped sequence the human genome, Ed Catmull the co-founder of Pixar and John Green, who wrote one of the best selling books of all time, all have aphantasia.

“So it definitely means no sensory imagination. But yeah, because that's such a loaded term, we tend to just say, without visualisation or there’s a great term that I like to use – image free thinking. It's kind of a different spin on it, and maybe you know not everyone will love that.”

For many aphants, it’s hard sometimes to come to terms with how it can impact their life. The creation of Ebeyer’s website came at a time when there was no content about it, no sense of community and a lot of people confused trying to figure out what it meant. The idea of visualisation if you don’t experience it, he says, is easy to romanticise.

“How nice must it be to see images of loved ones in your mind, and especially as someone who can't visualise and doesn't really know what the experience is like. It's very easy, I think, to get caught up in all that and mourning the loss of something that you never had.

“I would say, for me, there was grief for quite a long time, and I'd be lying if I didn't say that there are still some days where I'm like, of course, it would be amazing to visualise. I lost my mom when I was in high school. She passed away suddenly. And I think about that kind of stuff. I wish I could kind of replay memories we had as a kid, because I remember details and concepts but I can't relive it in any way.

“I can't imagine the sound of her voice. It's not just pictures we're talking about, the majority of people can experience imagination with all of the senses.

“For me it's like I don't have pictures. I don't have sounds. I don't have smells, or touch or taste whereas other people do, or have some kind of combination of the different kind of mental senses.

“I’m in a much different place about it now. If someone were to offer me a pill and say take this and you'll visualise forever, I probably wouldn't take it, because I think one of the things that it took me a while to understand as someone who doesn't visualise is that for most people mental imagery has a large, involuntary component meaning.

“Sometimes people see images in their minds that they don't necessarily want to be seeing. Maybe they went through some kind of traumatic event or some kind of stress in their life, and then those images won't leave them and come up kind of organically and without their control.

“When I discovered people visualise, I initially thought of it more like a computer screen, where you can kind of control it and cycle through the images and stuff. But the majority of people don't really have that kind of control. And when I think about that I'm like… you know, I don't know what it would be like. Imagery seems to be a bit of a double-edged sword in some cases, and there are some advantages to not visualising.

“I've switched my perspective on it because of some of those ideas that I've learned about.”

In the past

Ebeyer talks about sports psychology, as an example, and the fact that many athletes use visualisation techniques in their training and races. An interview he had with a sports psychologist who discussed a runner helped him rethink his perspective.

“The runner tripped during a race in college and now every time he goes to run, all he sees in his mind is that image of himself, falling, and so their whole work together, their whole sessions are all about him getting over this picture in his mind that keeps coming back.

“I've done embarrassing things and failed at things in the past. Those are in the past for me. They’re not conscious or present with me in any moment. They're kind of things that I left behind. Hopefully I learned from them. Of course there are positive things that would be great to relive. But most people in life have negative things that maybe they don't want to relive. In some cases, you know, people relive them without the choice. And that's a really interesting kind of difference.”

Psychedelics and visual imagery

Read up on the topic in any way and two subgroups always come up – congenital aphantasia and acquired aphantasia. The former are those born with it, the latter is like the patient in Zeman's paper who could previously visualise but after surgery could not. They are important distinctions in the larger research area because some studies are exploring whether psychedelics like DMT may temporarily restore visual imagery.

It’s quite early, however, and there are conflicting reports. A 2018 article in the Journal of Psychedelic Studies, Ayahuasca Turned On My Mind’s Eye, starts with some background stating “preliminary evidence in humans suggests that hallucinogenic or psychedelic drugs that act as angonists of cortical 5-HT2A receptors enhance visual imagery”. It suggests the first reported case of a person with aphantasia using ayahuasca, reporting improvement in visual imagery following “ingestion of a single dose of the South American botanical hallucinogen ayahuasca, which is rich in DMT".

David Luke, Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Greenwich, responded to the article, suggesting that the distinction between acquired and congenital aphantasia be further explored concerning psychedelic use.

“There is a sub segment of people who could visualise earlier in their life and they went through either an emotionally traumatic event or a physical trauma. So some kind of brain injury and they acquired aphantasia. It seems to have more of an effect in helping those who have acquired aphantasia to visualise again.

“I get hundreds of emails in my inbox basically every week from folks who are discovering they have aphantasia and psychedelics is, at least a recurring theme. It doesn’t, from what I've heard anecdotally, seem to have the effect that people are expecting.”

Research areas

Depending on what research you read, roughly 1.2-2.1 per cent of the population has aphantasia but with research in its infancy there’s clearly a need to differentiate between acquired aphantasia and congenital aphantasia.

“This is a huge area of interest for researchers going forward because obviously that is a clear distinction between different subgroups, and that kind of tells you a lot about what causes it and what you can do about it.”

Building the community on aphantasia.com has always been a top priority for Tom. He holds monthly research presentations with people studying aphantasia who share their findings. One of the big initiatives he’s working on to launch later this year is focused on connecting people who struggle to explain aphantasia to a therapist or counsellor, whose techniques often require visualisation.

“I get these stories of people who tried to talk to their therapist about this and said ‘they just didn't even believe me’, or ‘they looked at me with this blank stare’. One of the things we're trying to do is build some kind of directory where folks looking to speak with someone about it can do that.

“There is some good data on this – about 30 per cent of people who discover they they don't visualise have some kind of a psychological stressor about it. They feel like they're missing something… they're going through a grief period and many of them do want to talk to somebody.

“So we're building out a little program around that to try and connect some of the professionals who are aware of aphantasia and have dealt with those kind of clients before.”

To learn more and take the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire, visit aphantasia.com and to find out more about the new directory:

For professionals: aphantasia.com/join-directory/

For individuals seeking support: aphantasia.com/find-support/