Political response to ADHD

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is widely misunderstood, often perceived as a mental illness which has an impact exclusively on children. In fact, it is a debilitating neurodevelopmental disorder which can persist well into adulthood.

The issue is further complicated by the fact that it can present in different ways. This piece looks at the huge challenges faced by people with the condition (or their parents) to access adequate support and services, and what political response may be available.

The challenge for policy makers is that ADHD appears now to be increasingly prevalent, yet there remains a reluctance, to the point of outright opposition in some instances, to address it properly and to provide adequate support and services.

Waiting times

In Northern Ireland, diagnosis of ADHD is practically non-existent within the public health system: official waiting times are five years for children and eight years for adults, a period of time during which no one can afford simply to sit around. The practical impact is that people may seek diagnosis privately, but this then may or may not be recognised by GPs or others within the public system. Ultimately, many people’s experience is that the public system does not cater for ADHD at all.

This lack of service, in itself, has a serious detrimental impact. If we were left simply to wait for diagnosis, everything from access to vital medication to adequate school or workplace provision would become practically impossible. In practice, provision for children who show symptoms of ADHD is through Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), but as it is not in itself a mental illness it would be preferable for provision to be made via neurodevelopmental pathways.

Challenge for parents

Many parents of children with ADHD (whether diagnosed or undiagnosed) are told directly that their child does not have a mental illness, and that ultimately treatment in practice can only be effective via the necessary medication – which is a challenge if either the parents cannot access that medication or if the child refuses to take it. For adults, provision barely exists at all – hence the existence of this blog!

Sadly, the story of lack of provision as experienced by people with ADHD has parallels elsewhere in Northern Ireland’s health system. Although the condition is very different, the practical battle with the authorities faced by people with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME; also known as “Chronic Fatigue Syndrome”) is not dissimilar. They too have faced challenges ranging from outright lack of recognition from health professionals through to a practical absence of adequate diagnostics or treatment. People with rare conditions often tell similar stories of a battle simply even to be heard, while pursuing improved support and services.

In an era of departmental silos and restricted budgets, what can political leaders do in response to these huge challenges?

Recognition

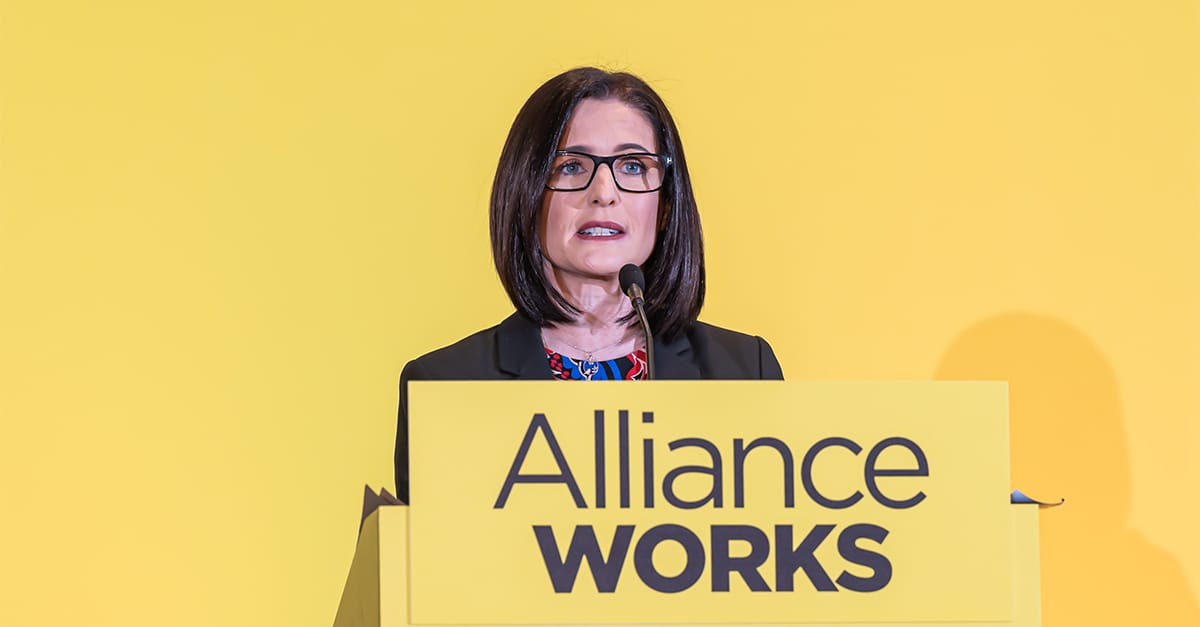

The starting point has to be recognition. We now see wider awareness, evidenced for example in Assembly Questions, of ADHD and of the challenges associated with it. My party colleague Peter McReynolds recently ran a petition to raise awareness of the need for services specifically for adults. The issue has become mainstreamed, and that is a step forward.

In recent meetings with the Department I have been told by officials that their priority is to provide support for the individual in front of them. This is not an unhelpful response, given that the impact of ADHD on any given individual can vary considerably. If the Department is saying that it is focused on a “patient-centred approach” to people presenting with ADHD symptoms, that is a good thing.

Nevertheless, some of this work does still jar with the tendency, for example, to treat ADHD effectively as a mental illness, a bracket into which it simply does not fit. In many instances, recognition of its impact and high-quality information on how to manage with it would make a considerable difference, but casting it as a mental health issue in many instances is unhelpful.

Early intervention

Ultimately, as with many other areas of policy, the health system needs to recognise that intervening early to diagnose ADHD and provide adequate and bespoke support services will provide considerable value, not just in alleviating the impact on people and families immediately but also in ensuring early intervention which may prevent serious issues arising in later life.

As so often, there seems an unwillingness to recognise that the response to a particular health issue needs to be restructured and modernised to improve outcomes in terms of immediate response, precisely to restrict bigger problems occurring down the line.

It is important for people living with ADHD to tell their story where they can. Public sentiment is shifted more readily by narratives than by statistics. Blogs such as these will play a critical role in the development of an improved response to ADHD by public authorities, in terms of diagnosis, support and service delivery.