Losing my religion

Exploring the relationship between autism and aphantasia helped me understand why Catholic rituals felt distant and faith was never a good fit for me.

Religion plays no part in my life now that I'm an adult. Growing up in the late 1970s as an Irish Catholic in the North of Ireland, religion was more than theological differences. It was, and often still is, about identity tied to history, politics and culture.

In some ways, I still identify as Catholic when pushed to answer the question because agnostic atheist doesn't quite roll off the tongue as easily. The rare times I do say it, or choose it in a drop down menu, I'm not talking about transubstantiation or papal infallibility. I'm saying something about my cultural background. Albeit that background is a complex mix, given that before the age of 22, I'd lived on three different continents – from the Falls Road to New South Wales and the suburban sprawl of Cranberry Township, Pittsburgh.

My family moved to Australia in the late '80s and it was here that it felt like Catholicism was suddenly rammed down my throat. I was 12, so maybe it was no different than it had been in Belfast, but I certainly felt it. In hindsight, maybe it was simply an overcompensation from my parents for being more than 10,000 miles away from the politics, history and culture that's intertwined with the word Catholic.

We lived in a single storey green panelled house that was a few minutes walk from Our Lady Queen of Peace in Greystanes, a suburb of Western Sydney. At least it was easy to find the Irish family, the green building standing out in a row of brick houses.

We had to kneel nearly every night and pray in our living room, whilst making the short guilt-laden shuffle to the end of the street to go to Mass on a Sunday. I always feared if the curtains weren't drawn someone would look in, see me perform that ritual and it would make me stand out even more than simply someone whose accent was constantly misunderstood. And it was constantly misunderstood. I once asked for a box of floppy disks at a store and the staff pissed themselves laughing asking what a box of floppy desks was.

A few years later, we moved back to Belfast. Shortly after arriving home, Michael Stipe played Losing My Religion live for the first time at the 40 Watt Club in Athens, Georgia and Goodfellas hit the cinemas, though I wouldn't watch the latter until years later.

When I finally did watch as Ray Liotta's character described how he always knew he wanted to be a gangster, it made me think about my own certainty – but in reverse. While Henry Hill was drawn to his world from childhood, each passing genuflection pulled me further from religion. I was as confused by the notion of a higher power as Tuddy Cicero was by Hill wasting "eight fuckin' aprons" on the mailman.

Donuts, a metaphor for faith?

In my late teens, I was finally trusted to go to Mass without my parents. Having passed my driving test, my girlfriend at the time and I would buy some chocolate donuts at a nearby shop and sit in my car in the church's carpark until the stream of Mass-goers would start to filter out, their bellies not as full as ours before we'd drive back home. There's probably something in what they'd just eaten being plain and symbolic and ours being sweet and indulgent.

Looking back now, those Sunday mornings in the car feel like a perfect metaphor for my relationship with religion... I was physically present (if you count being in a carpark) but mentally elsewhere, choosing concrete experience over abstract belief. It's only since understanding I'm autistic and have aphantasia that I've started to make sense of why traditional religious practice never quite clicked for me.

While Mass is rooted in all the senses – the smell of incense, the sound of hymns, the texture of the host and the physical merry-go-round of kneeling, standing and sitting – it's also heavily focused on visualisation and abstract thinking.

Visualising the invisible

As someone with aphantasia, the Rosary and the ability to picture each Mystery in your mind as you pray or having to 'close your eyes and picture yourself in God's presence' presented quite an interesting challenge given I can't picture anything in my mind's eye.

Throw in the consecration where we're meant to imagine bread and wine literally becoming Christ's body and blood, whilst somehow retaining their physical appearance and my mind is blown. When you can't create mental images and your brain seeks concrete explanations rather than metaphysical ones, much of this becomes an exercise in confusion rather than connection.

It makes sense to me today that I struggled with the metaphysical aspects of Catholicism. A study by Caldwell-Harris et al. suggests some autistic individuals may tend toward more mechanistic thinking patterns. That fits with my own experience – analysing systems and patterns over emotional cues and social beliefs.

The research, which primarily examined analytic cognitive styles and their relationship to atheism, included correlations with autism. It linked this to a tendency toward analytic or logical cognitive styles, which often clash with the abstract and symbolic thinking associated with religious belief.

Finding clarity in code

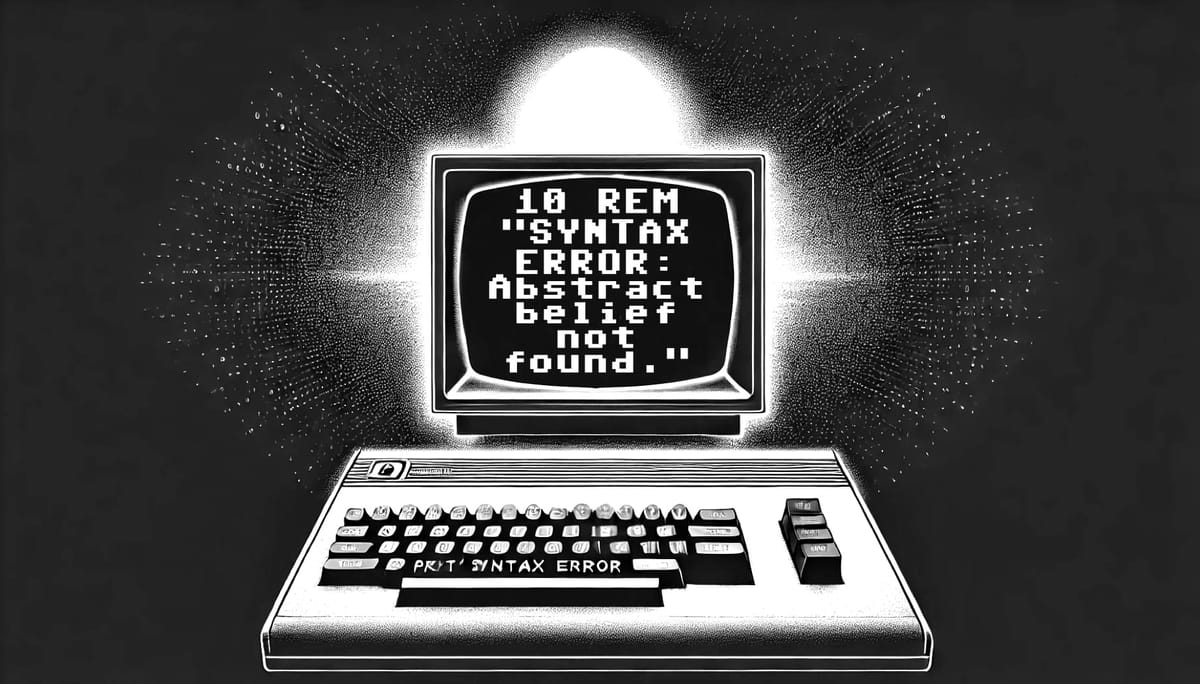

During my first Christmas in Australia, I got my hands on a Commodore 64 and fell in love with programming in BASIC (hence me needing a box of floppy desks). That was me at my mechanistic best – understanding the world through concrete systems where specific inputs create predictable outputs. Enter the right code, get the right result... or sometimes in my case enter the code get a ?SYNTAX ERROR. It was, however, simple – clear rules with clear outcomes.

For me, mechanistic thinking is like programming – you want to understand the exact system, the specific rules that make things work. Mentalistic thinking is more about understanding things through emotions, intentions and beliefs. For the latter, it's less about the code and more about why someone wrote it in the first place.

This difference in thinking styles becomes really interesting when it comes to religion. Most religious concepts rely heavily on mentalistic thinking – understanding an unseen deity's intentions, interpreting symbolic meanings, or feeling a personal connection to a higher power. In BASIC, every GOTO statement had a destination – something I found far more reassuring than unanswered prayers.

The 2011 study suggests that autistic individuals are generally less likely to engage in organised religion, though the reasons are complex and varied. Caldwell-Harris' research found autistic participants were more likely to identify as atheist (26% vs 17%) or agnostic (17% vs 10%) compared to the predominant neurotype. Perhaps most interestingly, autistic individuals were nearly three times more likely to construct their own religious belief systems (16% vs 6%).

The comfort of letting go

The limited research out there paints an interesting picture of autism and religious belief. While some autistic people find comfort in religious rituals and clear moral frameworks, the data suggests a trend toward questioning traditional religious concepts.

The study's data of higher rates of atheism and agnosticism among autistic individuals, combined with the tendency to create personal belief systems rather than accept traditional doctrine, suggests that many of us process religious concepts differently than our predominant neurotype peers.

Like all aspects of the autistic experience, this is not one size fits all. Relationships with faith and spirituality are deeply personal. Some individuals find profound meaning and connection in religious practice, while others, like myself, have followed different paths.

In the final scene of Goodfellas Henry Hill complains about having to "live the rest of my life like a schnook". But while Hill mourned losing the identity he'd had since a young age, I've found freedom in stepping away from mine. These days, when someone asks if I'm Catholic, I'm comfortable saying agnostic atheist... turns out being a 'schnook' isn't so bad after all.